There have been many recent theories regarding the name and meaning of Sambor Prei Kuk. On the world heritage nomination, it is translated as “the temple in the richness of the forest.” Another issue was raised among Cambodians as whether Kuk should be written as guh with a silent “h” or guk with a “k”. This because modern Cambodians only understand Kuk, ending with a “k”, as “prison” not the other meanings employed by villagers across Cambodia and northeast Thailand to refer to small and nameless towers. I have offered my opinion in the previous post. Regarding the meaning of Sambor Prei Kuk, Michel Tranet had offered a rendition as “la foret aux tours” or “the forest of towers.” As the confusion persisted, particularly, after Sambor Prei Kuk became a World Heritage site, I wish to settle the topic with this short article.

The purpose of this current article is to trace the history of such a strange name, Sambor Prei Kuk, bore by a Cambodian site. While Prei Kuk, Prei Prasat, or Prei Kdei are common names for sites in Cambodia, which simply means “the forest of temple” or ” temple forest;” to have an adjective or a noun, a qualifier, Sambor (“plentiful, richness, abundance”) in front of Prei Kuk is unique. The form renders the translation as “the abundance of the temple forest,” which ambiguously refers to the abundance of either “the temple” or of “the forest.” Hence, the translation “the temple in the richness of the forest,” which is yet another form of ambiguity. That because the name itself is a half-breed, a French invention! Let me show you why:

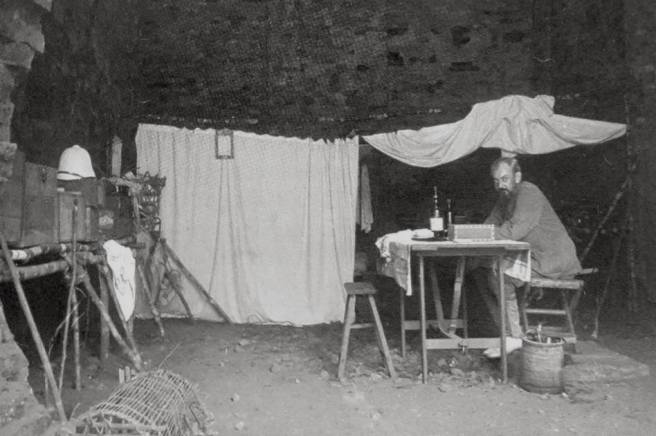

We shall travel back in time to the period between 1894 and 1928 when French researchers began their serious exploration into archaeology, history, and epigraphy of Cambodia (figure 1). These efforts led them to a group of brick temples in Kampong Thom (known as Kampong Svay or Soay at the time). Was Sambor Prei Kuk used at the time? Let us look at ten relevant sources:

- Adhémard Leclère (1894:372): Prasat-kuk (with en dash “-“)

- Étienne Aymonier (1900: 372): Sambuor

- Lunet Delajonquière (1902: 225): Sambuor

- Henri Parmentier (1913: 21-22): Prei Kuk

- Louis Finot (1912: 184 [footnote 1]): Sambuor or Saṃbór

- Arousseau (1922:90): Sambor Prei Kuk (without en dash “-“)

- Jeanne Leuba (1925): Sambor-Prei Kuk (with en dash “-“)

- Henri Parmentier (1927: 44-46 [footnote 1]): Sambor-Prei Kuk (with en dash “-“)

- Victor Goloubew (1927:489-492): Sambor-Prei Kuk (without en dash “-“)

- Louis Finot (1928:42-46): Saṃbór Prei Kŭk (without en dash “-“)

The name can be traced to “3 footnote clashes” between Henri Parmentier (an architect) and Louis Finot (a Sanskritist) over the course of 17 years between 1911-1928 (pardon my rusty translation, I have not used French since 2005!):

Henri Parmentier (1913: 21-22), in his footnote 1: “The name of this location is Saṃbór, pronounced Sambo but with the O as short as possible. The name is easily confused with another Sambór [that is Sambor of Kracheh, emphasis added]. To avoid the issue, Lajonquière accepted another vicious form, Sambuor. I believe that it is preferable to adopt the indigenous name applied to these ruins: Pràsàt Prei Kŭk, “The towers of the forest of Kŭk.” The Cambodians generally applied the term Kŭk small pràsàts.”

Louis Finot, in his footnote 1 of the “Nouvelles inscriptions cambodgiennes” (1912: 184 [1]) in the “Inscriptions de Sambuor” section, wrote: “It appears that the verifiable name of the village is Sambór and that the ruins are called Prei Kuk. This last name, which was not known to neither Leclère [this is partially true! Although Prei Kuk was not used, Adhémard Leclère already called these temples Prasat-Kuk, emphasis added] nor Lajonquière, is perhaps a name politely invented by the locals to satisfy the last explorer [i.e., Parmentier, emphasis added]. There is no need to substitute a more interesting village name with this banal name. Sambuor or Sambór must indeed correspond to Śaṃbhupura.”

Fifteen years later, in his “l’art khmer primitif“, Parmentier (1927: 45-46) responded yet with another footnote: “The locals give no name to these monuments, which they hardly know and rarely worship. Their ignorance is so great that they have shown only a part of it and very minimal to Lajonquière… when the inhabitants of Saṃbór finally understand what we are talking about and stop denying the existence of any nearby pràsàt, they acknowledge that there are some ruins in the “Prei Kŭk”. It is probable that one of the first European visitors who named this group based on the neighboring village, Sambor, modified it incorrectly as Sambuor, a name unknown in the region. It appears preferable to adopt the closest designation to that of the locals and to avoid either retaining the unknown form of Sambuor or being confused with Sambor of the River [i.e., Kracheh, emphasis added]. The simplest way, to avoid any difficulties and not to lose the memory that may be retained in the name Sambor (Śambhupura?), is to adopt the double form Saṃbór-Prei Kŭk, which has no other inconvenience than its length.”

Note that an en dash “-” was used as “or” in Parmentier’s (1927) proposition, that is “Sambor” used by the previous publications followed by an en dash, then an indigenous name of “Prei Kuk” reported later by Parmentier. The current form of Sambor Prei Kuk, without an en dash “-” or any Romanized characters can be attributed to Victor Goloubew who carried out a clearance within the Southern Group in 1927. In his “Nouvelles inscriptions du Sambor” Finot (1928: 43) accepted Saṃbór Prei Kŭk (without an en dash “-“) as employed by Victor Goloubew (1927). I am not sure how L. Arousseau fits into this narrative; however, he seems to refer to Parmentier’s work. Jeanne Leuba, or Mrs. Parmentier, was at Sambor Prei Kuk with Parmentier since their first trip in 1911 and in this newspaper article she reported of another trip with Parmenter again in 1916. It is, thus, quite likely that both Henri Parmentier and his wife, Jeanne Leuba, came up with a reconciliatory double-name of “Sambor-Prei Kuk” many years prior to Parmentier’s major publication of l’art khmer primitif in 1927. Likely by the time Bernard-Philippe Groslier worked here in the 1960s, an acronym SPK was introduced to this complex.

There you go! The parents of the name “Sambor Prei Kuk” were Henri Parmentier and Louis Finot! A Khmer rendition of the name should be similar to this form: “Sambor Kracheh” (i.e., Sambor of Kracheh) or “Banteay Srei Damdek” as opposed to “the Banteay Srei“. Then, “Prei Kuk Sambor” or Prei Kuk of Phum Sambor would sound less strange. Thus, the translation of Sambor Prei Kuk is simply “the forest of towers of/at Phum Sambor.” Nevertheless, the form Sambor Prei Kuk has been used since 1927 that any change is unnecessary other than to acknowledge its history.

I hope I have settled the confusions surrounding the name “Sambor Prei Kuk”! Two other parallels shall be mentioned here. The first concerns a ceramic kiln complex located on Phnom Kulen, east of Angkor. It has been known by the locals since the time of Aymonier’s visit as “Thnal Mrech” or “Sampov Thleay.” However, researchers in the 1990s named the same site according to the village name of “Anlong Thom.” I wrote in a joint paper (Miksic et al 2009) that:

“Specific kiln locations are known to locals as Sampov Thleay (‘wrecked ship’) or Thnal Mrech (‘pepper road’) in current terms and oral history. Local names should be adopted for purposes of clarity of identification, location, and interpretation. Therefore we use the local name Thnal Mrech Kiln Site or TMK rather than Anlong Thom for the excavated entity described in this report. The name Thnal Mrech literally means ‘road of pepper’ (Piper Nigrum Linn). Phnom Kulen means ‘mountain of lychee’ (Litchi chinensis Sonn. Nephelium litchi Cambess) probably a reference to the abundance of such trees on the plateau. Sampov Thleay’s place name suggests a Chinese origin for ceramic deposits there.”

During our research in 2007, Chhay Rachna and I have argued that the name should be reverted to Thnal Mrech. Nonetheless, to reconcile with other articles and authors, we have settled with Thnal Mrech (a.k.a Anlong Thom) (e.g., Chhay et al 2013). It does not seem to be too late though; it has only been 20 years! The second example is the renowned “Lapita culture” of the region located in Near Oceania and western Remote Oceania. The name “Lapita” was given to a site in New Caledonia in 1956 by archaeologists. According to Sand et al (1998), it was the corruption of a local name Xapetaa, which bearly sounds like Lapita!

The take away point here, try your best to use the local name! Yet also be aware that in many instances, sites in Cambodia are known more than one names! I think the best solution is to use the most popular name and acknowledge other variations in a footnote.

Honolulu 12 July, 2017

Piphal Heng

References cited:

- Arousseau, L. 1922. “Lettre de M. G. Groslier et Réponse de La Rédaction Du Bulletin.” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 22: 389–91.

- Aymonier, Étienne. 1900. Le Cambodge: Le Royaume Actuel, Vol 1. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

- Chhay, Rachna, Piphal Heng, and Visoth Chhay. 2013. “Khmer Ceramic Technology: A Case Study from Thnal Mrech Kiln Site, Phnom Kulen.” In Materializing Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Volume 2, edited by Marijke J Klokke and Véronique Degroot, 2:179–95. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Finot, Louis. 1912. “Notes d’archéologie cambodgienne.” Bulletin de la commission archéologique de l’Indochine 1: 183–93.

- Finot, Louis. 1928. “Nouvelle inscriptions de Sambor.” BEFEO 28: 42–46.

- Goloubew, Victor. 1927. “Chronique: Sambor Prei Kuk.” Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient 27: 489–92.

- Lajonquière, Lunet de. 1902. Inventaire Descriptif Des Monuments Du Cambodge, Vol 1. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

- Leclère, Adhémard. 1894. “Fouilles de Kompong-Soay (Cambodge).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 22 (5): 367–378.

- Leuba, Jeanne. 1925. “Le groupe de Sambor-prei kuk,” March 18. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k7554234q.

- Miksic, John N., Rachna Chhay, Piphal Heng, and Visoth Chhay. 2009. Archaeological Report on the Thnal Mrech Kiln Site (TMK 02), Anlong Thom, Phnom Kulen, Cambodia. ARI Working Paper 126. Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

- Parmentier, Henri. 1913. “Complément à l’inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambodge.” Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 13 (1): 1–64.

- Parmentier, Henri. 1927. L’art khmèr primitif. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. Paris: Librairie nationale d’art et d’histoire.

- Sand, Christophe, Karen Coote, Jacques Bole, and Andre Ouetcho. 1998. “A Pottery Pit at Locality Wko013a, Lapita (New Caledonia).” Archaeology in Oceania 33 (1): 37–43.